Dissertation Defense, Jan 2019

Lightly edited remarks from my dissertation defense on 25 January 2019. Check out the Afrasian Imaginaries playlist (Spotify) while you read.

And, please, stay for the acknowledgements at the very end of this rather long post. I’ve been working on them since I finished coursework and they have been a life force in carrying me to the end. I could not have done it without all of you, my audiences and communities. Nor would I have wanted to.

Dhow Meets Container Ship in the Indian Ocean near Unguja (Aug 2017)

Thank you to everyone who has gathered here to share in this milestone with me. I’m a joiner and by virtue of your proximity to me, I have made you join me in this journey. Whether you’ve been here from the earliest iterations of this project — of making life bearable for me in western Mass — or if we have gotten to know each other more recently, thank you for thinking and with me about these ideas; for reading my writing with me; for doing pomodoros with me. I wasn’t built for the silo of our profession and you’ve made it such that I didn’t have to live and work that way. There really aren’t enough words for that. My mom often tells me that when one is off beat — as I am in both music and life — we travel alone. You all being here counters that notion. I have not had to travel alone.

“The story of “Afrasian Imaginaries” is a migrant narrative.”

To tell this story well, we need to indulge in time travel. When I was 9, my family moved from Karachi, Pakistan, to Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, so that my parents could attend medical school. Their school was a cosmopolitan place: their classmates seemed to come from every point in the world. They included black and brown South Africans, Nigerians, Kenyans, Black Americans, Sri Lankans, Indians. If during the colonial period, cities and educational institutions in the Global North were meeting points of the colonized from across the world, then, in the contemporary, Santo Domingo seemed one such site. What I remember most is how my mother frequently claimed that Santo Domingo was just like Karachi. This rubric of familiarity is not a common trope in many immigration narratives, certainly not the ones most of us are familiar with. And I wonder now if the familiarity we found in the DR can be reduced to the contemporary. What other sedimented histories are there that make the Caribbean familiar to us Pakistanis?

The affordances of this double diaspora movement — if I might call it that — from Pakistan to the Dominican Republic to the United States — didn’t click for me until I became a student of postcolonial fiction and theory in college. It is only retrospectively that I can order the story this way, applying the analytics of migration studies, to notice my own journey as more circuitous than those represented in stories of South Asian immigration to North America. The stories that involve the Caribbean have been relegated to a different historical period, the nineteenth century, and claimed as part of a different colonial narrative.

Naomi Darling and Darrell Petit’s “Solar Time” (Fall 2018)

Unlike the forced, or coerced, labor diasporas of that earlier period,

my journey is marked by choices and opportunities. Or, at least, that’s the story I have long been told.

Liz Glynn’s Archaeology of Another Possible Future,

Mass MoCA (Dec 2018)

The project of the postcolonial nation-state and migration in the aftermath pivot around promises of inclusion, which today means inclusion into a system of global capitalism that announces itself in the modalities of flexibility (see: opportunities and choices earlier). However, such promises either increasingly remains unfulfilled for the globally marginalized, or were never meant for the dispossessed, or disposable, across the world. One of the artifacts of such disposability is the container ship, containers themselves. As I wrote “Afrasian Imaginaries” I found such containers all over the world, as restaurants in Puerto Rico and Durban; as malls in Dubai and Johannesburg. They have also been vehicles for transporting bodies across securitized national borders as rendered in the fiction of Amal Sewtohul and Ghassan Kanafani to name two writers and as the real live stories of numerous anonymous to us who, in attempts to escape the ongoing violences of colonialism and imperialism, smuggle themselves abroad in these containers. This is the logic — aesthetic and political — of late capitalism.

Adan Paredes, Image Title Unknown, Museo de Los Pintores Oaxaqueños

Images on a wall where a former maroon community resided near Santiago de Cuba (July 2012)

The imbrication of earlier South Asian diasporas in the Caribbean — even if not exactly in the Dominican Republic — made me curious about the other lesser told stories of migration, contemporary and historic. In the project that became “Afrasian Imaginaries,” I followed my curiosities to a somewhat more familiar geography, the Indian Ocean. Nadine Gordimer’s 2001 novel, The Pickup, which I read in my first year of graduate school played a critical role in helping me cultivate the notion of a circular migration, one marked by continual returns, or at the very least a non-linear route in which one quite literally ping pongs from country to country. Issues surrounding citizenship and belonging—questions of mobility, of freedom, of rights—resurfaced during my study abroad in Cuba during the summer of 2012. Focusing on Afro-Cuban and Afro-Caribbean literatures, histories, and cultures gave me the opportunity to think more expansively about a range of relationships between colonizers and colonized peoples, including alliances between colonized peoples. Specifically, writing a paper on Martin Delany's Blake, or the Huts of America that I presented at an annual pan-Caribbean scholarly and cultural conference in Santiago de Cuba sharpened my understanding of nineteenth century abolitionist movements in the Americas; in turn, I developed a much keener sense of earlier eras of globalization. Thus, it was the Atlantic World and more specifically the Black Atlantic that led me to the Indian Ocean to think together multiple histories, cultures, and literatures that are divided often by Cold War era Area Studies models of knowledge production.

These days, a return to oceans seems timely as waters rise across the globe and these arenas become renewed sites of militarization, much like they were during the colonial period. Perhaps, they have never stopped being. Following earlier networks of trade and exchange, oceans are once more pathways for renewed global partnerships. For instance, China’s multinational partnerships across Asia and Africa under the banner of the One Belt, One Road flaunts its relationship to the historic Silk Road and millennia old Indian Ocean maritime networks. All that was old seems new again.

“Afrasian Imaginaries” highlights representations of living and laboring across the Global South through twentieth and twenty-first century cultural texts from African and Asian Indian Ocean communities. These texts circumvent Eurocentric center-periphery binaries, offering counter narratives that elucidate the longstanding cultural and economic exchanges of the Indian Ocean World.

The Indian Ocean becomes an agentive body, a facilitator and disrupter of Afrasian exchange that allows me to work alongside histories of colonialism, anti-colonial resistance, and postcolonial nationalism without the obligation of a linear route from colonized to free that articulates itself through the manifestation of the nation-state.

I recast narratives of global capitalism that foreground systems of trade and exchange that refuse to assimilate easily into the prevailing notion that EuroAmerican modernity created capitalism and imposed it upon the formerly colonized world. I argue that Indian Ocean fictions and theoretical perspectives use multi-layered histories of the region as a resource to re-articulate relationships across the ocean’s littoral.

Toward representing the plurality of Indian Ocean lifeworlds, “Afrasian Imaginaries” includes Anglophone works from several different contexts that are supplemented by works in translation from Gikuyu and Malayalam, languages from Kenya and India respectively. It also features a balance of perspectives between a younger and older generation of writers. At all points, I have strived to craft a project that, in the words of Julietta Singh in Unthinking Mastery, “distance[s] ourselves from mastery” and “reframe[s] [my] relations to all things” and “[f]rom this point of departure, directionality becomes infinite” (175).

Captions on individual stills read as follows:

“Everyone here supports Brazil. The true supporters are all here.”

”We love Brazil because they love football like we do (in Lyari).”

”Similarly we support West Indies in cricket — they are black like we are!”

As the intellectual biography of “Afrasian Imaginaries” attests, my life has been shaped to a significant degree living alongside and in black history, in the afterlife of slavery. The shape of the terror that conjoins my life to the geohistories of blackness become material in our shared, and differentiated, relations to colonialism and capitalism. These days, I think of these moments as waves, as histories that come close to one another that are not replicable but nevertheless approach and then move away from one another. I consider “Afrasian Imaginaries” to be a black study of Indian Ocean lifeworlds for this mode of scholarship has taught me how to fracture calcified knowledge. Dropping anchor in Indian Ocean studies, harnesses its plural temporalities, illuminates the multiplicity of centers and how these centers are mutually constitutive. It demonstrates how a singular center need not dominate. Drawn together, these margins refuse center-periphery models of knowledge production and circulation. Instead, through critical practices such as wake work and intimacies, stories forgotten or erased re-emerge as do their protagonists and the worlds they inhabit.

Lest this journey engender a romantic retelling of my own story, let me say explicitly that this work is marked by a profound pessimism but I am not dismayed by it. Indeed, in that way I am driven by an enduring commitment to the struggle toward abolition of heteropatriarchal racial capitalism even if I, myself, may not experience a world otherwise from this one.

I like a big audience because we do not do this work alone.

And, who could’ve guessed that there would be a huge RESIST banner hanging on the windows. The serendipity of it all. 😍

Commencement, May 2019

All the shout outs to some of the very best faculty at UMass English, Drs. Ron Welburn, Asha Nadkarni, and Rachel Mordecai. So special to have all three of them at commencement. And, cheers to my fellow freshly minted doctor friend, Lauren Silber.

Truly thrilled to celebrate with my mom and aunt (there’s a very similar picture of us in front of Radio City Music Hall in May 2007). I wouldn’t have made it through this year without Marwa and Sean’s help and humor (thanks, fam!). And, then super stoked to share this moment with my cohort mate, Greg Coleman, and my friend Nii Kotei Nikoi, who defended his dissertation just that week. Nii is also the fabulous photographer of the dissertation defense photos and several photos here.

Also, can we please talk about how Haathi looks better in my regalia than I do? That’s what we call patriarchy at work: when your male dog fits into your ceremonial robes better than you do.

It’s a doctor party!

First, with my favorite doctor, the one who can answer actual 911 calls.

Lauren and I are definitely about to launch a podcast and I’m still sassing my aunt.

OK, I’m sorry but actually not sorry at all. My advisor is literally the best. A million billion thanks to Asha for always having my back.

Here’s five of us doctor friends, scientists, social scientists, and humanists all together. Two more soon to be doctors. Sean in classic toast mode with an audience that indulges him.

🥳🥳🥳

Next Stop: Greensboro, North Carolina

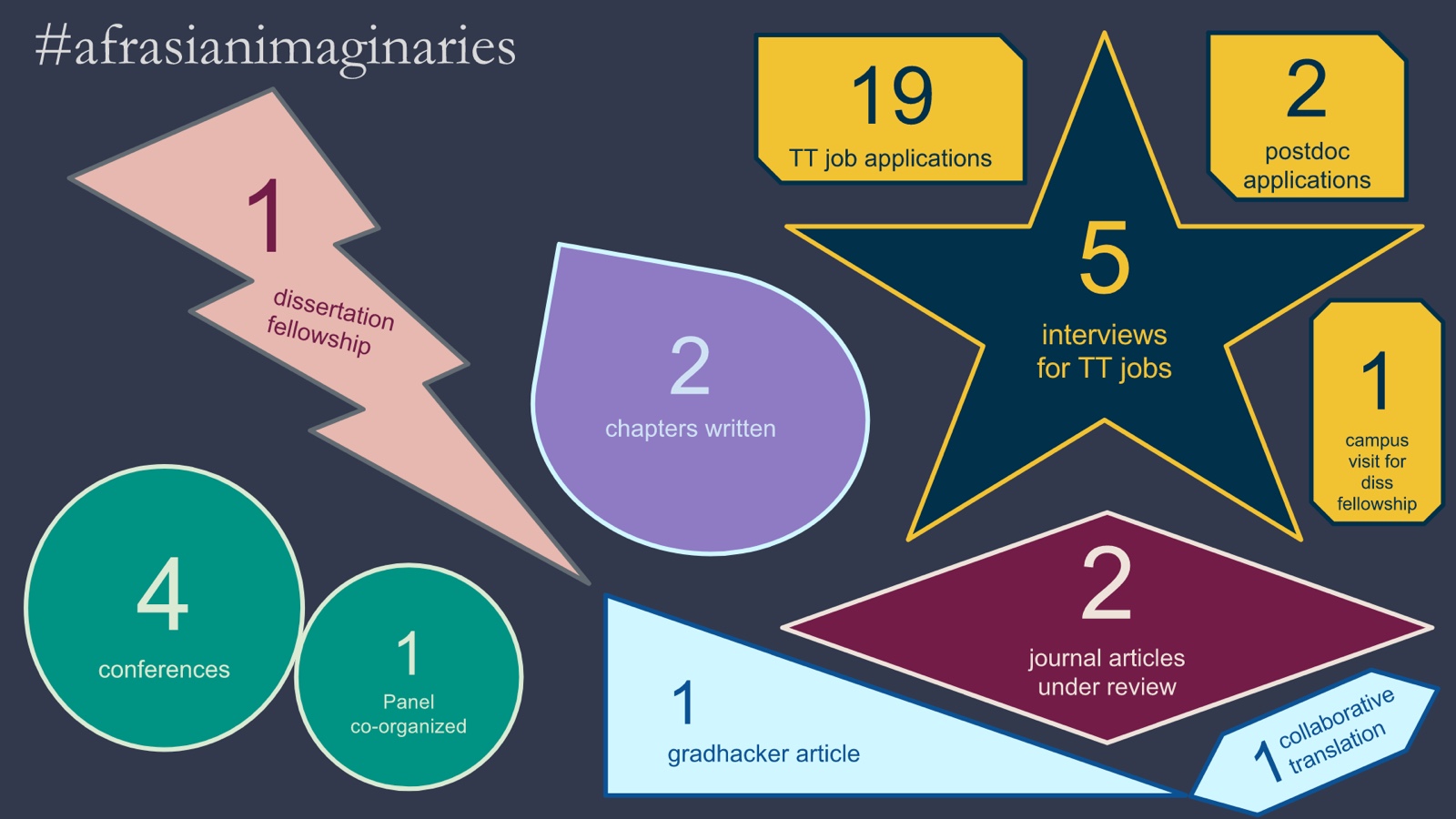

Now that all the ink is really really dry on the digital contracts and I have found a place to live, it’s finally starting to feel real that I got a job! A job that I am incredibly excited for 🦄

In August 2019, I’ll join the faculty at UNC-G as

Assistant Professor of English and International & Global Studies.

I’m grateful to join a minority serving institution, a place where my colleagues have welcomed me so warmly already, and a place where I’ll get to support both undergraduate and graduate students.

It’s actually a dream come true!